Irish proverb: The most beautiful music of all is the music of what happens.

Fort Bragg

Northern California is the place on earth that I love most, and I wander into its outer reaches from my home in Berkeley as often as possible. Most recently my husband and I and our Labrador, Dulcie, spent some time in our fifth-wheel trailer in Fort Bragg, a coastal town in Mendocino County. Port Silva, the fictitious town that serves as setting for my mystery novels, is not precisely Fort Bragg; but Fort Bragg is Port Silva's—template? progenitor? inspiration? We've been camping there, or thereabouts, for many years.

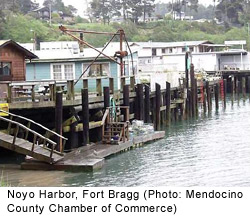

Fort Bragg was originally a fishing and lumbering town; there's a fine small harbor and marina, and until recent years a vigorous lumber mill occupied a long stretch of the handsome coastline. When we first began to visit there, the harbor was busy with commercial fishing. In the present day, however, many—perhaps most—of the boats going out from the harbor carry people fishing for sport or watching for whales.

Lumbering, too, has declined. The mill ceased operating some time ago; now the city, the Georgia-Pacific owners, and coastal authorities are trying to decide just how, and by whom, that piece of prime real estate will be used. The town needs commercial activity, of course; you can buy food and books and art and hardware in Fort Bragg, but not much in the way of ordinary clothing, or furniture, or large household items. However, the lifeblood of the town, as in the picturesque village of Mendocino to the south, is probably going to be tourism. Well, tourism and retirees, who are sparking a modest boom in second homes as far north as Westport.

So things are changing. The old bridge taking State Highway One over the Noyo River (called Pomo River in my stories) has been since 1948 the only way into Fort Bragg from the south. Now there's a big new bridge, safe and beautiful. Locals watched the construction carefully and made such a fuss when the original plans blocked the view of the estuary and ocean that CalTrans agreed to change the plans; and now, as with the old bridge, you can still see the view while driving or walking or biking across. An aside here: upcoast a ways, where the bridge that makes a lovely swoop across the Ten-Mile River has been declared unsafe, a similar struggle is taking place.

So things are changing. The old bridge taking State Highway One over the Noyo River (called Pomo River in my stories) has been since 1948 the only way into Fort Bragg from the south. Now there's a big new bridge, safe and beautiful. Locals watched the construction carefully and made such a fuss when the original plans blocked the view of the estuary and ocean that CalTrans agreed to change the plans; and now, as with the old bridge, you can still see the view while driving or walking or biking across. An aside here: upcoast a ways, where the bridge that makes a lovely swoop across the Ten-Mile River has been declared unsafe, a similar struggle is taking place.

There are new restaurants in town, and older restaurants are offering more sophisticated menus and preparations. The site near the wharf occupied for many years by a collection of raggedy-ass house trailers is now a vast empty space. Earlier signs, as I recall, promised a spiffy new trailer park; signs posted there now announce that a number of nice new homes (presumably houses) will appear there soon. In fact, it appears that much of the old, slightly raffish, and individual in Fort Bragg will be replaced by the new and tidy. Necessary for tourists and incomers, I suppose; but I'd think that for at least some of the locals, the changes will be unsettling. And what has happened to the people who once lived in those old trailers?

A short way north of town, a large state park and campground have occupied the ocean edge for many years. Not much will change there, probably, because California parks are wildly underfunded. To some extent, the same is true of much of the north coast: the Coast Highway is narrow and winding, the weather often chilly and foggy, and storms off the Pacific can wipe out electricity several times each winter. But north of the park, the tiny town of Westport is having a tiny building boom of large, obviously new or extensively renovated houses right on the coast. A small park is under construction on the bluffs there as well, and a square old two-story building dating from 1880, according to large numerals on its facade, is being refurbished—as a hotel, maybe? The contrast between those impressive buildings and the small, elderly houses set east of the highway is almost comical, at least to the casual driver-by.

As an outsider, a sometime-visitor, I have no right to strong opinions about any of this. But in our state's distant, beautiful places, people whose families have lived and worked through three and four generations have at best mixed feelings about tourism and second homes. "No, we don't have any ski resorts here," said a man I met one day while hiking in the Trinities. "No resorts, no stop lights. Because there's no money here, and that's the way we like it." He put his fishing pole over his shoulder, whistled up his dog, and strode on down the trail.

And an author's note: Yesterday I spent most of a day at the annual Fine Crafts Fair in at Fort Mason in San Francisco, wearing my feet out on concrete floors and my eyes and senses out looking at booth after booth of wonderful, individually-made jewelry, glassware, clothing, pottery, metal-work, stringed instruments. As I lusted after various pieces of fine hand-crafted wooden furniture so beautiful I couldn't resist stroking some of them, I heard one of the wood-workers talking about his craft. It turns out that designing and making beautiful furniture—or probably jewelry or clothes—is not that different from crafting a story; the process can wake one up in the night as a new idea strikes, and send the maker to typewriter, or chain saw, to try to bring the dream to reality. This simple fact had never before struck me so clearly.

—Janet LaPierre

Return to the current Music of What Happens

© Janet LaPierre.